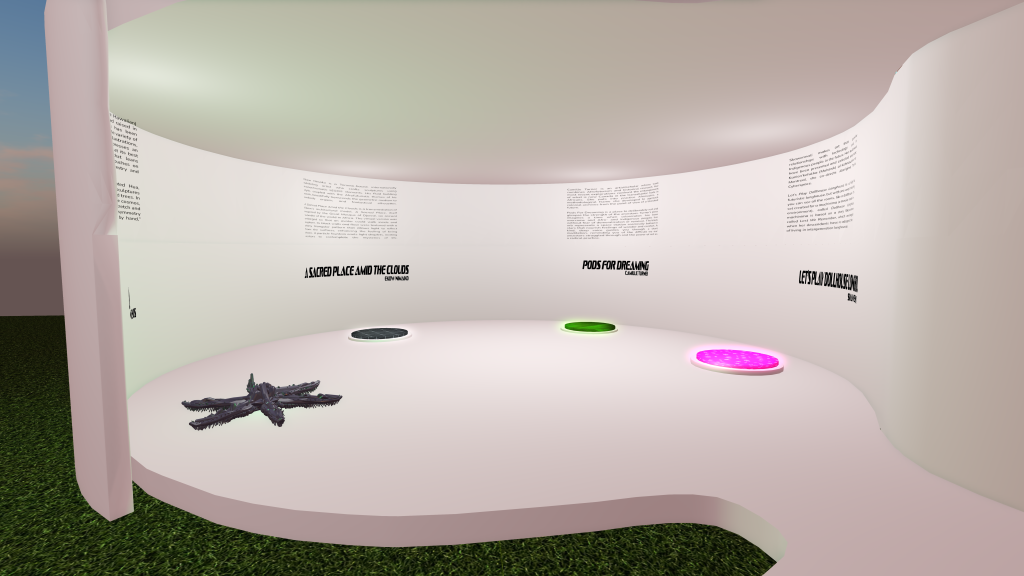

We See Far is a virtual exhibition of works by four artists, Camille Turner, Solomon Enos, Ekow Nimako and Skawennati, who have for decades been envisioning futures in which our peoples thrive.

The moment an artist sets out to depict the future, they must interrogate the past. What is our creation story? What are our accomplishments? How did we think, talk, live in earlier times? How do we want to think, talk and live in the future? Historical research is a foundational element of each of these artists’ practices, as is science-fiction. Mixing these two frameworks is the basis of the both Afro Futurism and Indigenous Futurism

Indigenous Futurism follows in the footsteps of the more established Afro-futurism movement. Both pull from our rich cultural heritages and imagine what we might look like in speculative futures or alternate worlds where, perhaps, colonization never happened. Or maybe there was a revolution. Or an evolution. Many evolutions!

The countries that these artists are based in, Canada and the United States, were, we know, built on the labour of slaves stolen from Africa and land invaded and cheated from Indigenous nations. And while the effects of those histories continue to felt today, there is more hope than ever that through activism and education, wrongs will be righted. If Afro- and Indigenous people have been strong enough to survive the attempted genocides, imagine what we can do if we work together. We See Far is a step, after many that have gone before, and certainly many that will follow, towards that work.

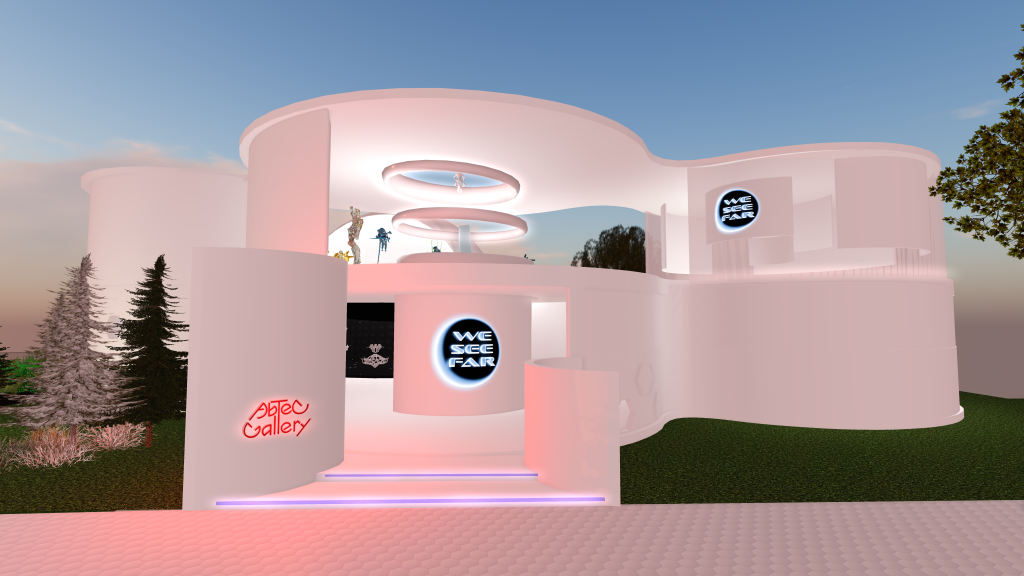

AbTeC Gallery has been in existence since 2020, when the pandemic forced everyone to go virtual. As we worked with some 45 artists to port their work from physical media to digital, we became excited by the virtual versions of the work. Artists were delighted when they realized we could easily, with a simple click-and-drag mouse operation, move walls, add an extension, remove a ceiling. No one had to worry about temperature or about people breaking the artwork. We wondered what was possible, and got a grant to explore the idea and practice of transmediation, the process of translating something from one medium to another. We assembled a small team of multitalented Research Assistants who have expertise in the massively multiplayer online world, Second Life; 3D modeling; animation; video; and sound work.

Solomon, Ekow and Camille had never before worked with Second Life. Skawennati invited them to be part of the exhibition with the conviction that virtual worlds are futuristic medium and that their art would make sense in its context; and with the offer of the expert team to assist them in transmediating their art. They rose to the challenge!

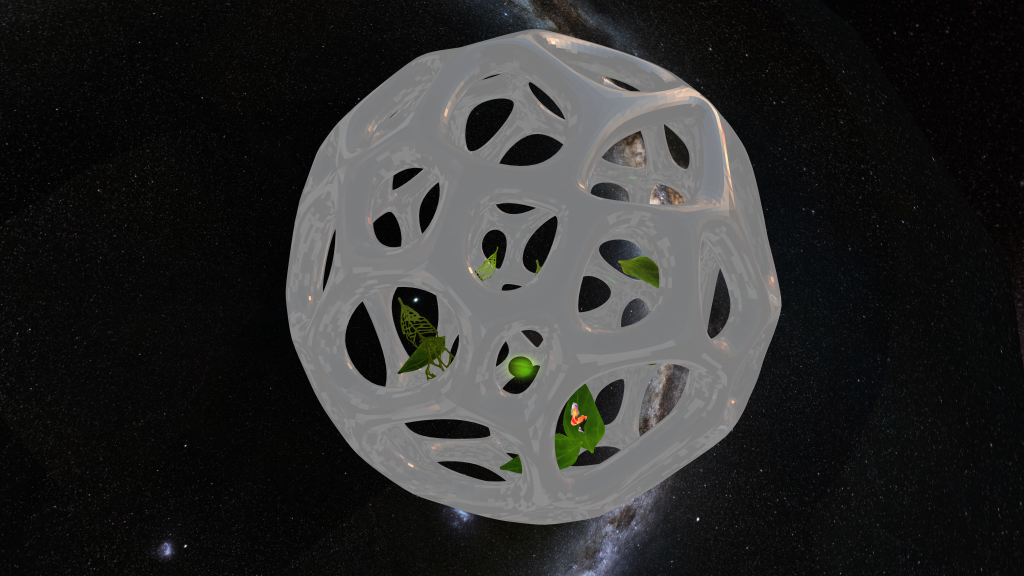

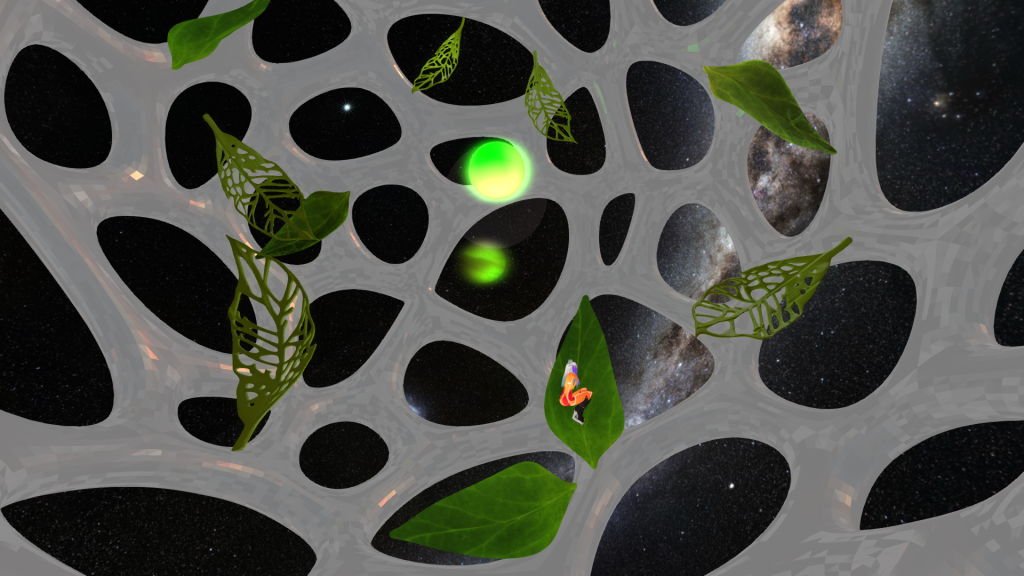

When the team met with Camille, she told us she’d been trying to figure out some way that she could create a place where people could leave behind the weight of the world and simply float and dream. Because virtual worlds can bend certain physical laws, like gravity, her vision was entirely possible. Thus began Pods for Dreaming, an artwork that imagines a a time when colonization has been overcome and Afro- and Indigenous peoples live without fear of demoralization or removal. But freedom must be continuously protected, which takes energy. So Camille has created a unique site where you can go to rest, recharge and glimpse the strength of the ancestors. Using your avatar, you enter this location from a teleport station in the gallery. As soon as you click it, you are inside a silver, hollow, and net-like orb through which you see the starry sky of outer space. A sound piece is playing. A kind, deep voice guides you through a short meditation, reminding you of the difficult era our ancestors struggled through–a time when they “could not breath”–and then leading you through a deep inhale and exhale. Around you are a number of pods, in the form of giant green leaves. Text hovering above each leaf invites you to “click on leaf to dream”. Doing so causes your avatar to lie down & curl up on the leaf. The piece nods to the idea that rest is resistance, a manifesto put forth by Tricia Hersey, itself a speculative work that wonders what it would be like to live in a well-rested world.

Besides defying gravity, creating virtual artworks offers other perks including the ability to modify the scale of an object.

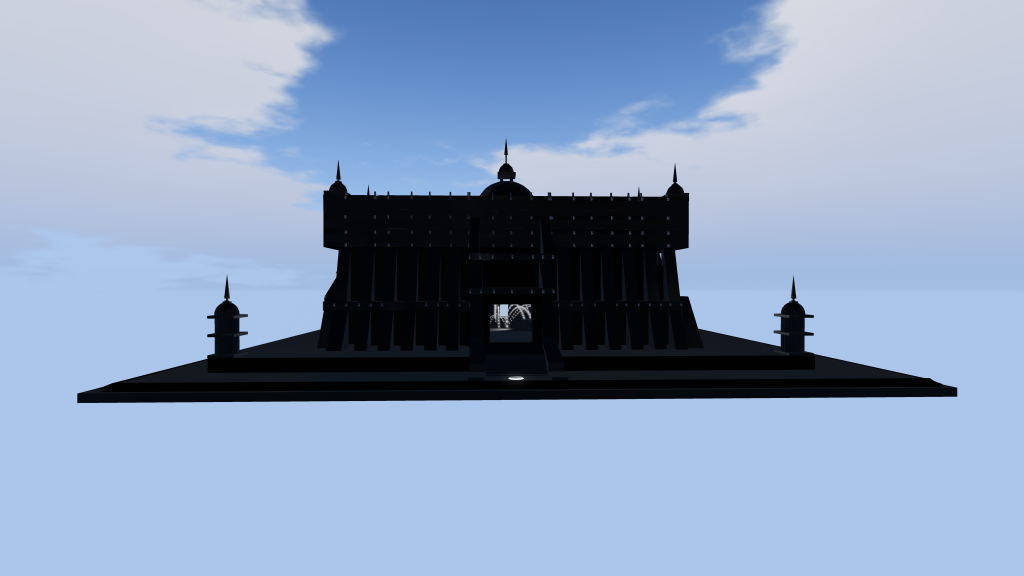

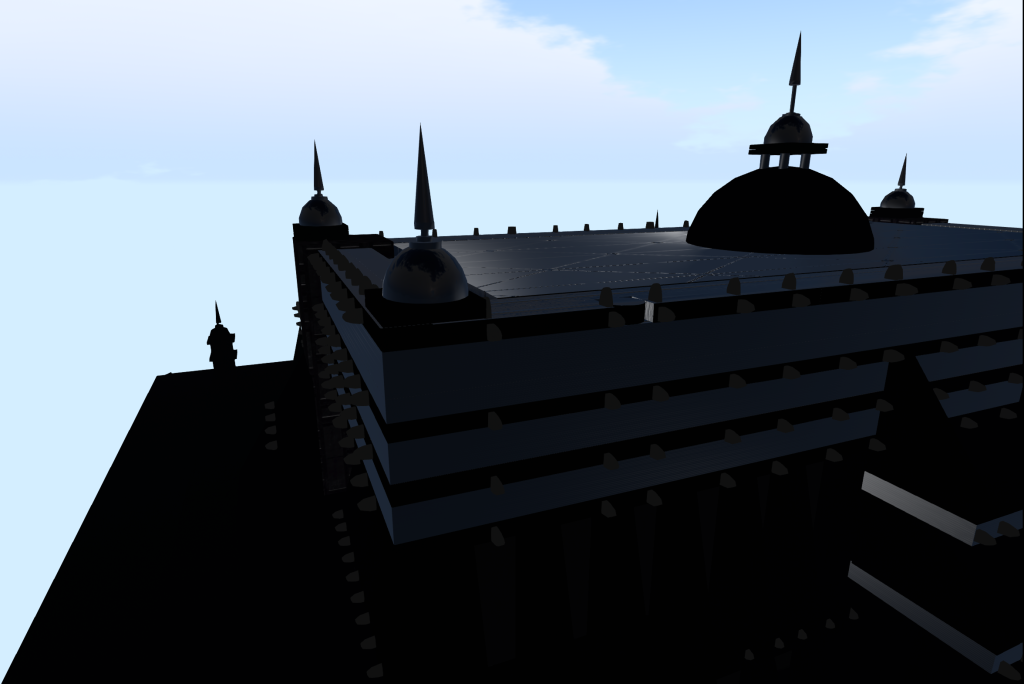

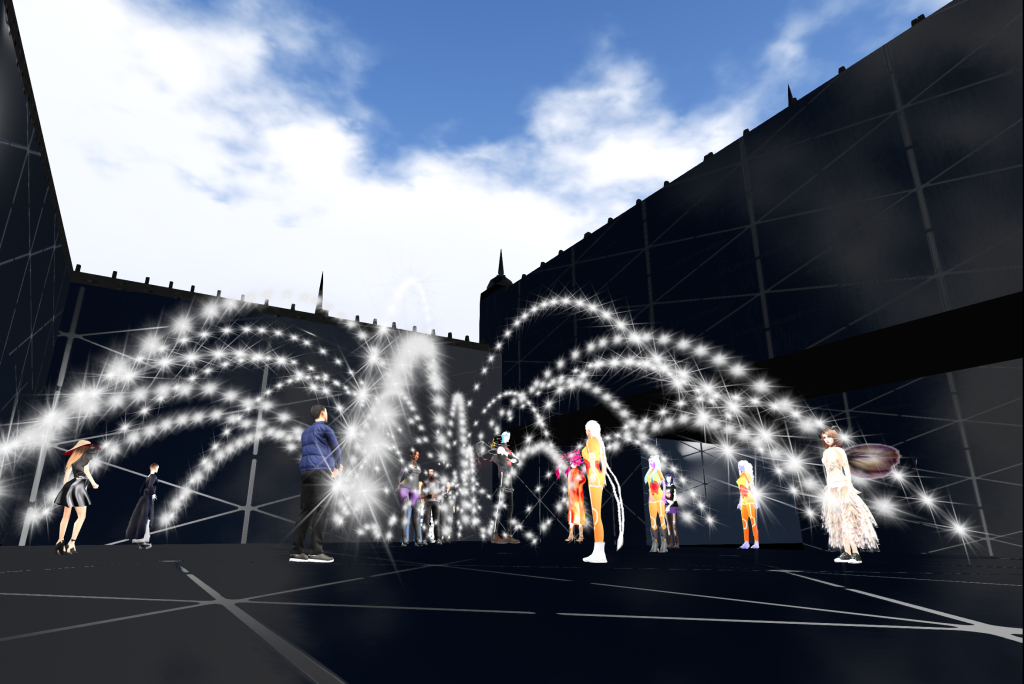

Ekow Nimako is known for his intricate sculptures made of black monochromatic Lego, usually black. His larger-than-life fantastical figures, as well miniature models of entire cities, point to a future where Black and African people rule their own societies. Together, the artist and the AbTeC Gallery team decided to transmediate his sculpture, A Sacred Place. In its physical form, this piece is a relatively small architectural structure inspired by the Great Mosque of Djenné, an ancient wonder of the world located in West Africa. For We See Far, this work was scaled up so that avatars could walk through its doors. Operating an avatar in Second Life generates a sense of embodiement that mimics –surprisingly well– the sense that you are actually in a location, and so you feel as if you are in this mythical place that Ekow created. We placed the building high up in the sky, added a celebratory light-particle fountain, and adjusted the environment. It is titled, A Sacred Place Amid the Clouds.

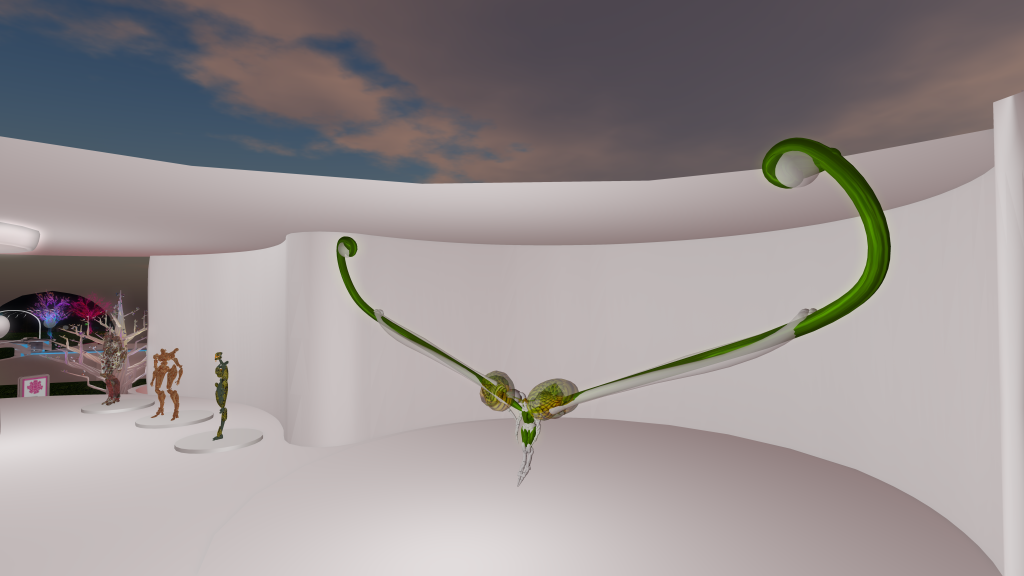

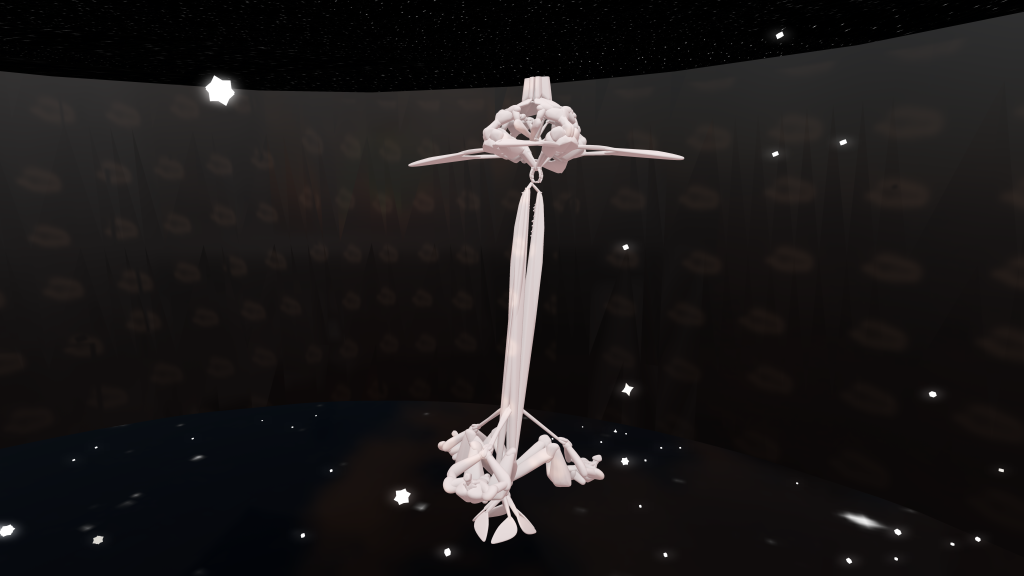

While Second Life is a powerful platform, it can’t do everything. You cannot, for instance, create organic forms using its building tools. However it is possible to upload forms created with other software. Solomon Enos used this method to make Hua, an ongoing series of sculptures that imagines that humans one day evolve into plant-beings. “Hua” is a Kanaka Maoli (Native Hawaiian) word meaning seed or egg. Solomon imagined a future where these vegetal humans can be transplanted onto other worlds. As they grow, they adapt to their new environment, taking on a multitude of forms. A selection of the sculptures have been placed throughout the gallery. There is the star-like seedpod resting in the teleport room; untextured sculptures of groups of beings in flower-like formations in the room with the disco ball; a green humanoid with the two giant tendrils growing from its back upstairs; and more.

Skawennati created a domestic space that recalls childhood memories while, of course, looking towards the future. Let’s Play Dollhouse Longhouse is based on a text which she was asked to write by the Guild of Future Architects, which would imagine life in the year 2100. That story, “Lest We Remember” considers the great revitalization project currently taking place in Indigenous communities throughout North America (and beyond): grass-roots organizations and universities alike are finding the resources to offer language classes, beading circles, hide-tanning camps, heritage seed swaps and more. This work imagines what it would be like if we revived the practice of living together in intergenerational longhouses.

From the teleport room, you are brought just outside the longhouse. The building is smooth and white, with one door on each end. You see that one side is open, like that dollhouse you wish you had when you were a kid. A kitchen, dining table, and living room complete with fireplace comprise the first floor. A staircase leads to a sewing studio, bedrooms and a tiny bath room. Instead of dolls, we now have avatars to pretend that we are living there. Take a look around, have a seat by the fire, go upstairs and take a bath, if you like!

The four artists in We See Far look ahead to times when we can overcome the traumas of oppression, to the times when we will be our best selves. Bringing these visions into conversation with each other furthers our ancestors’ efforts towards a more joyful and just world.